We see a lot of venomous snakes in the field. Think of it as an occupational hazard.

A Red Spitting Cobra at Lothagam, Kenya

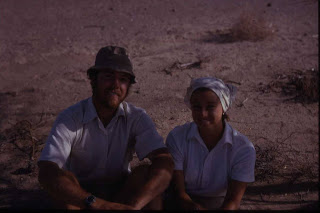

What follows is a favorite story I tell to my family and friends. They cannot disbelieve me, because Susan was there and never stretches a story. It's called "The stick got up and slowly walked away". This is the short version:

On the way to Kenya for field work we stopped at the British Museum of Natural History to examine fossils from India. Humphry Greenwood, the curator of the fish collection, heard where we were going and asked us to check a

Nothobranchius locality well north of Malindi, near Lamu.

In Kenya we borrowed one of Princeton's Toyota Land Cruisers, and a seine net, for the trip. We obtained a permit from the Kenya Fish and Game Department (now Fisheries) for "Scientific collection of freshwater fishes", demanding all specimens to be deposited with the Kenya National Museum. This works; since museums routinely loan research specimens to other museums, the British Museum folks would have easy access to the specimens.

The first night we camped in Tsavo National Park, because the night was so dark that I nearly hit a Zebra on the road. In camp our sleep was interrupted twice. First when the night passenger train to Mombasa passed nearby. Steam locomotives are loud!

Then about 2 am a herd of Elephants walked through our camp. We sleep in the covered truck bed , so there was no danger of being stepped on, but they startled us. We could hear their breathy wheeze, "Whee-uw! Whee-uw!"

In the morning there were huge piles of Elephant dung around as we made our breakfast. We broke camp about 7 and continued toward the coast.

At noon we stopped at a small duka and bought great Samosas and cold Tusker beer for lunch. We drove into Mombasa, then turned North along the coast road for Malindi. We stopped at dusk at a beautiful beach campsite north of Malindi. Many dutch hippies were in attendance; they were much disliked by the staff because they never bought anything or tipped. They were glad to see "rich americans" for a change.

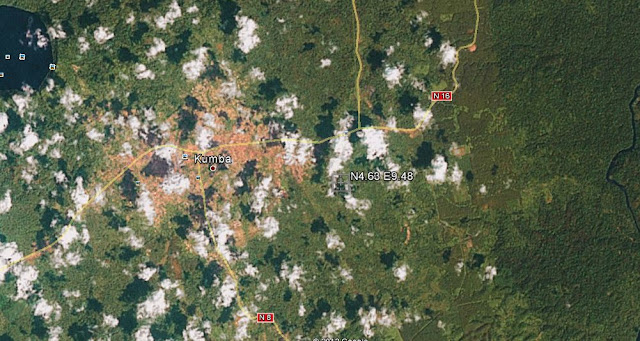

A temporary pond, a "pan" has formed along a low spot in the road. This pan was full of hundreds of killifish related to

Nothobrachius guentheri, shown below.

The next day we left for the northeast coast, where we collected and preserved Nothobranchius from coastal pans. On the way we passed through several police checkpoints. Late in the day, at a pan on the edge of the coastal forest, Susan refused to get out of the truck to help seine. I had overlooked ten elephants at the edge of the trees, waiting patiently in the forest shadows for us to leave. They wanted their evening drink. I coaxed her out, leaving the doors open and the truck running. The elephants waited for us to finish, then went down for their drink.

A dusk we arrived at the little village that was our destination. Dull kerosene lanterns were lit in the dukas. We turned South to follow our directions to the locality of interest, but the road ahead was covered by thick mud; people walking were knee deep. I asked, in my newly learned Swahili, if we could drive to the intended area. A man said no, the bridge was out.

My map suggested a go-around, so we headed East instead. Soon we came to cleared land and artificial dikes, a bad sign. The locality, I feared, was destroyed. Two men were walking along the dike, and I asked if there were fish in the water. They said there had been "Samaki kidogo" , little fish, when they were young, but didn't know if any were left.

At the appointed location I stopped and turned the headlights on to illuminate the water. We walked with our net down the incline on the flanks of a big concrete culvert, and into a shallow channel. We found no fish of any kind. I've always thought that pesticides killed everything in the water. In disgust I led us back to the dike through tall grass. We walked back to the truck and I began to take notes.

In our headlights Susan noticed something in the road. Where we had just emerged from the tall grass she pointed to a long object and said "Chuck, there is a big snake in the road". I glanced up from my notes and replied "That's a stick". Susan said, "Well, the stick is crawling away". It was a big Puff Adder. I opened the glove box, and said "That's all right, we have Puff Adder antivenom". Just then the two men caught up with us. I cautioned them that a Puff Adder had just entered the tall grass on the side where they were walking. One replied "There are no snakes here."

We never found any

Nothobranchius in that spot, and so we made our way back to Malindi on the dirt highway. On the way the soldiers at one of the police checkpoints made us empty the contents of our truck at gunpoint. I became angry (I'm a Marine NCO), and Susan tried to quietly remind me of their rifles. Finally they explained that they thought we were ivory poachers. We were left to reload our truck without help.

As we drove back we saw several pythons on the road, and arrived at our beach campsite very late. Tired, we threw our low cots onto the beach sand and slept to the sounds of palm tree leaves rustling in the breeze.The next morning a fee collector shook us awake. He looked horrified and asked "Did you sleep in the open, on the ground?" We said we had, and he explained that Black Mambas come down from the trees every night to hunt. I guess we should have read the brochure.

That afternoon we telephoned our colleagues in Nairobi, and learned that a ring of thieves had stolen the other Princeton truck. By taking this side trip to the coast for the BM(NH), we had saved the expedition a great deal of money.

Notice: All of these posts and photos are copyrighted, with all rights reserved. Hundreds of friends and relations have seen them elsewhere for years. Don't even think about using them.